You’ve been there before. A patient walks in, points to a spot on their body, and says those four

frustrating words: “It hurts right here.” And thus begins your detective work. Is it a muscle? A ligament?

Something else entirely? Understanding the difference between contractile and inert structures isn’t

just academic trivia—it’s the foundation of effective physical therapy.

Introduction

Picture yourself as an anatomy detective. Your mission: to solve the mystery of your patient’s pain by

determining which tissue is the troublemaker. Is it something that actively contracts, or something that

passively exists to provide support? This distinction isn’t just semantics—it’s the difference between a

treatment plan that works beautifully and one that falls flat.

Getting this diagnosis right makes you look like a clinical genius (and yes, we all enjoy those moments

when patients look at us like we have X-ray vision). More importantly, it means your patients get better,

faster.

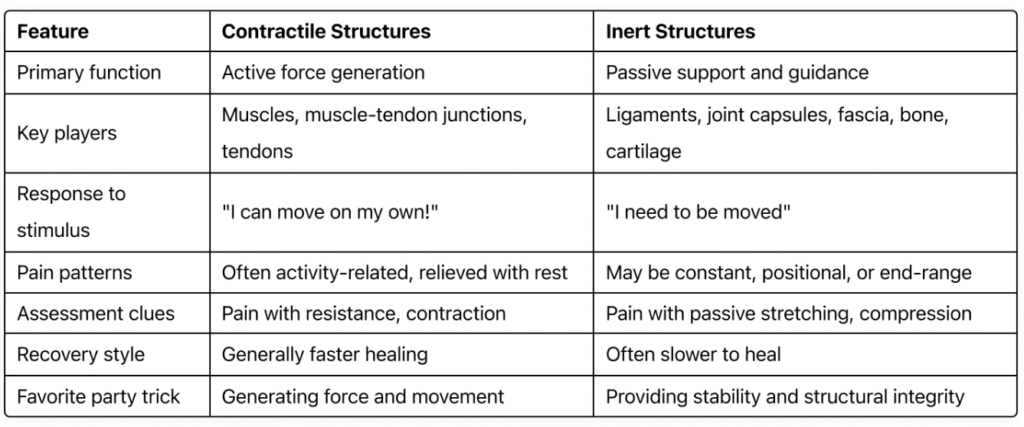

Contractile vs. Inert: The Ultimate Showdown

Before we dive deeper, let’s break down these two categories in a way that’s easy to reference:

Contractile Structures: The Movers and Shakers

Think of contractile tissues as your body’s action heroes. They make things happen. They’re dynamic,

powerful, and when they talk (through pain), we should listen.

The primary players in this category are muscles, the muscle-tendon junctions, and tendons

themselves. While only the muscle truly “contracts,” we consider the entire unit as contractile because

dysfunction anywhere along this continuum typically presents similarly in clinical assessment.

The secret language of contractile tissues isn’t that complex once you know what to listen for:

They hurt when they work (resisted movement pain)

They’re often tender to touch

They typically hurt more with use and feel better with rest

They respond relatively quickly to appropriate intervention

- They hurt when they work (resisted movement pain)

- They’re often tender to touch

- They typically hurt more with use and feel better with rest

- They respond relatively quickly to appropriate intervention

When contractile tissues go rogue, they announce it pretty clearly. That biceps tendinitis? It’s going to

bark when your patient picks up their coffee mug. The strained hamstring? Stairs become an

adventure. Contractile tissues rarely keep their problems to themselves.

Inert Structures: The Strong Silent Types

If contractile tissues are the action heroes, inert structures are the unsung support crew that keep

everything from falling apart. Ligaments, joint capsules, fascia, bone, cartilage, menisci—these

structures don’t generate movement, but try functioning without them and you’ll quickly appreciate

their value.

Inert tissues have their own language:

- They often hurt at end-ranges of motion

- They’re frequently position-dependent (hurts in this position, not in that one)

- Pain can be more constant or intermittent depending on positional stresses

- They typically take longer to heal than contractile tissues

The pain paradox with inert structures is fascinating—how can something that doesn’t move cause so

much trouble? The answer lies in their role as boundary-setters and weight-bearers. When

compromised, they fail at their primary job of providing stability and structure.

Neural tissue deserves special mention as a sort of “inert but irritable” wild card. While not contractile

in the traditional sense, neural tissue doesn’t quite fit neatly into the inert category either. It’s the

drama queen of tissues—highly sensitive, easily offended, and capable of referring pain in patterns

that make you question everything you learned in school.

Becoming a Tissue Detective: Cracking the Case

So how do you determine which tissue type is causing your patient’s problem? Through a systematic

approach that looks like an interrogation (but with better bedside manner).

The Questioning Phase:

- “What makes it worse?” (Activity-related pain often points to contractile issues)

- “Does it hurt constantly or only with certain movements?” (Position-dependent pain suggests inert

- structures)

- “Does rest help?” (Contractile tissues typically get relief with rest)

The Physical Examination:

- Resisted movement testing: This is where contractile tissues show their cards. Pain with resistance against a muscle contraction? You’re likely dealing with a contractile tissue issue.

- End-feel exploration: Inert structures often complain at end ranges or with specific joint positions.

- Special tests: These are your focused interrogation techniques. McMurray’s for meniscal issues, Empty Can for supraspinatus tendinopathy, etc.

Remember, tissues rarely read the textbook about how they’re supposed to present. That’s what

makes the next section so important.

Tales from the Treatment Table: Real-Life Mysteries Solved

Let’s put our detective skills to work with three common scenarios:

Case File #1: “The Shoulder That Wouldn’t Shrug”

The Mystery: Mark, a 45-year-old construction worker, presents with right shoulder pain that’s been

building for months. He can’t raise his arm above shoulder height without pain, and sleeping on that

side is impossible.

The Investigation:

- Pain with active shoulder abduction: Could be contractile OR inert

- Pain with passive end-range elevation: Points to inert structures

- No pain with resisted external rotation or abduction in neutral: Less likely to be rotator cuff

- Restricted glenohumeral joint mobility with firm end-feel: Classic capsular sign

- Pain relief with distraction of the glenohumeral joint: Another capsular clue

The Solution: While initially presenting like a rotator cuff issue (which would be contractile), the

absence of pain with resisted testing and the presence of capsular signs pointed to adhesive capsulitis

(frozen shoulder)—an inert structure problem.

The Treatment: Rather than strengthening exercises that would be appropriate for contractile

dysfunction, Mark’s plan focused on joint mobilizations, gentle stretching into pain-free ranges, and

gradually progressive mobility exercises.

The Outcome: Within 8 weeks, Mark had regained 80% of his range of motion and could sleep

through the night. His recovery continued more slowly (typical for inert structures) but steadily over

the next several months.

Case File #2: “The Back That Broke Bad”

The Mystery: Sarah, a 32-year-old office worker, bent down to pick up her toddler and felt a “pop” in

her lower back. Now she’s walking bent slightly forward and to the right, reporting sharp pain with

certain movements.

The Investigation:

- Antalgic posture (leaning away from pain): Could suggest either structure

- Pain with forward bending, relief with extension: Potential disc involvement (inert)

- No pain with resisted trunk flexion or extension: Less suggestive of muscle strain

- Pain with sustained sitting: Common with disc issues

- Positive straight leg raise with pain radiating down leg: Classic disc sign

The Solution: While Sarah initially assumed she had “pulled a muscle” (contractile), the assessment

pointed clearly to a disc issue (inert structure) with potential nerve involvement.

The Treatment: Instead of aggressive stretching (which could worsen a disc issue), Sarah’s plan

included extension-based exercises (McKenzie approach), gentle neural mobilizations, and education

on spine-sparing movement strategies.

The Outcome: Sarah’s symptoms centralized within 2 weeks (pain moving from leg to just back), and

within 6 weeks she had returned to most activities with minimal discomfort. Her posture normalized as

the disc irritation subsided.

Case File #3: “Knee Deep in Trouble”

The Mystery: Jason, a 28-year-old recreational basketball player, felt a “twinge” in his knee when

pivoting during a game. He reports pain primarily on the medial aspect of the knee, especially when

changing direction.

The Investigation:

- Pain with weight-bearing rotation: Could be meniscus (inert) or muscle (contractile)

- Minimal swelling: Could go either way

- No pain with resisted knee flexion or extension: Less likely to be muscle

- Positive McMurray’s test with reproducible click: Classic meniscal sign

- Pain with deep squatting: Consistent with meniscal issues

The Plot Twist: But wait! Further testing revealed pain with resisted hip adduction while the therapist

palpated the adductor insertion near the knee. This suggested a dual diagnosis—minor meniscal

irritation (inert) AND adductor strain (contractile).

The Solution: This case highlights how contractile and inert structures often conspire together. The

treatment needed to address both components.

The Treatment: Jason’s plan included protected weight-bearing activities to respect the meniscal

irritation while incorporating progressive strengthening for the adductor. The rehabilitation protocol

carefully introduced rotational forces as healing progressed.

The Outcome: Jason returned to modified activity within 3 weeks and full play within 8 weeks. The

contractile component resolved faster than the inert, as expected.

Treatment Playbook: Different Strokes for Different Folks

Now that we’ve identified our culprit, how do we approach treatment differently?

For Contractile Tissue Issues:

- Progressive loading is your best friend—these tissues respond to appropriate stress

- Begin with isometrics, progress to isotonics, and eventually incorporate functional movements

- Don’t fear early movement—contractile tissues generally need it

- Respect pain but don’t be ruled by it

- Focus on neuromuscular re-education to restore proper movement patterns

For Inert Tissue Problems:

- Respect healing timeframes—these structures typically need more time

- Consider protection phases more carefully

- Manual therapy often plays a larger role

- Progression must be more gradual and methodical

- Patient education becomes even more critical—these issues often require behavior modification

When Worlds Collide (Mixed Presentations):

- Prioritize which structure needs attention first

- Create phased approaches that respect both tissue types

- Be willing to adjust your plan as one component improves faster than another

- Use reassessment to guide progression

Clinical Wisdom (That They Don’t Teach in School)

After years in the clinic, you develop a sixth sense about tissues. Here are some pearls I wish someone

had told me earlier:

- The “that doesn’t make anatomical sense” moment is your brain’s way of telling you to reconsider your assessment. If pain patterns don’t match anatomical distributions, think again.

- Patients rarely present with textbook cases. Be comfortable with complexity and uncertainty.

- When a patient isn’t progressing as expected, the first question should be: “Did I identify the right tissue?”

- The timeline matters—contractile tissues typically show improvement faster than inert ones. If your patient with a “muscle strain” isn’t showing signs of improvement in 2-3 weeks, it might be time to reconsider your diagnosis.

Conclusion: Becoming a Tissue Whisperer

Differentiating between contractile and inert structures isn’t just about being right—it’s about being

effective. The power of precision in your diagnosis directly translates to better outcomes for your

patients.

As our understanding of tissue behavior grows, approaches will continue to evolve. But the

fundamental distinction between what contracts and what doesn’t will remain a cornerstone of clinical

reasoning.

Remember, at the end of the day, we treat patients, not MRI findings or special test results. The tissue

detective work we do is always in service of helping real people move better and feel better. And that’s

the most satisfying case to solve.